The first part of the this blog series can be found here.

A previous blog describes how in the summer of 2025 I spent time at Egrove Park, discovering how the site is used by an impressive diversity of bats. This blog provides more detail on usage of the site by two specific species: Daubenton’s and Barbastelle bats.

Note that the site is private, and my visits were made with permission. Do not visit the site without permission.

Credits

- Nick Bishop for the invitation and site access at Egrove Park.

- Merryl Parle-Gelling for advice and loan of an infra red video camera.

- Stuart Newson for supporting this activity with BTO pipeline credits and imparting his wisdom via the Bat Call Sound Analysis Facebook group.

Daubenton’s Bats at Egrove Park

Daubenton’s bat (Myotis daubentonii) is an insectivorous species that primarily feeds on midges, caddisflies, and other small insects captured over water surfaces. It typically roosts in tree holes, bridges, tunnels, and buildings located near aquatic habitats. Foraging usually takes place low over calm water, where the bats skillfully scoop prey from the surface with their feet or tail membrane. Commuting routes often follow linear features such as rivers, streams, hedgerows, and woodland edges.

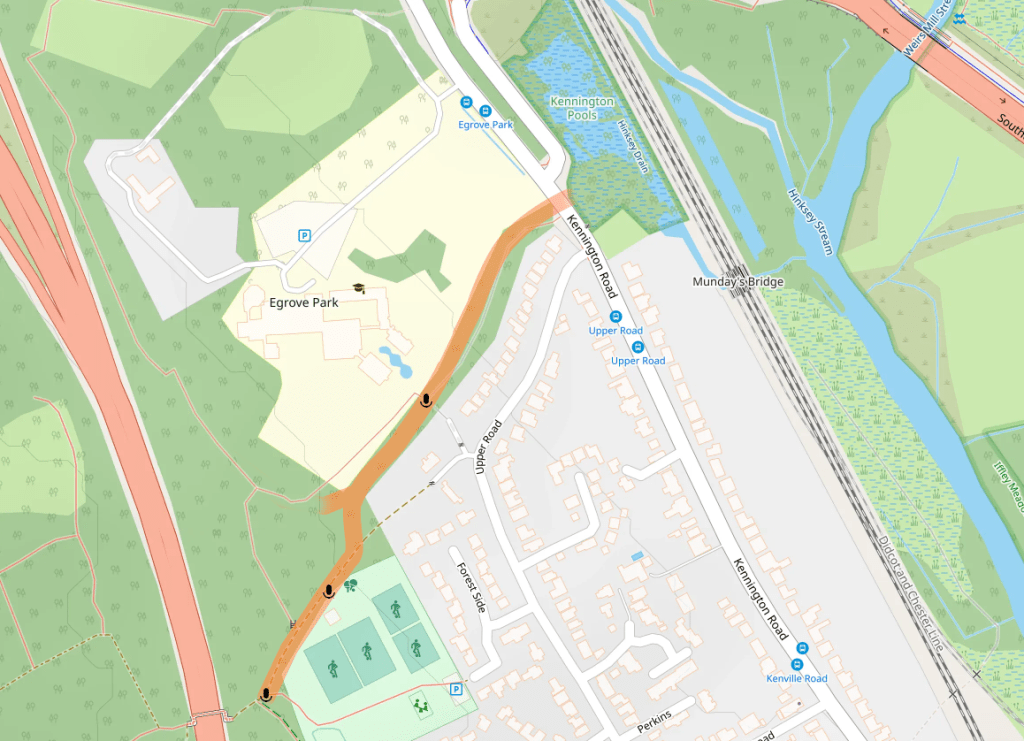

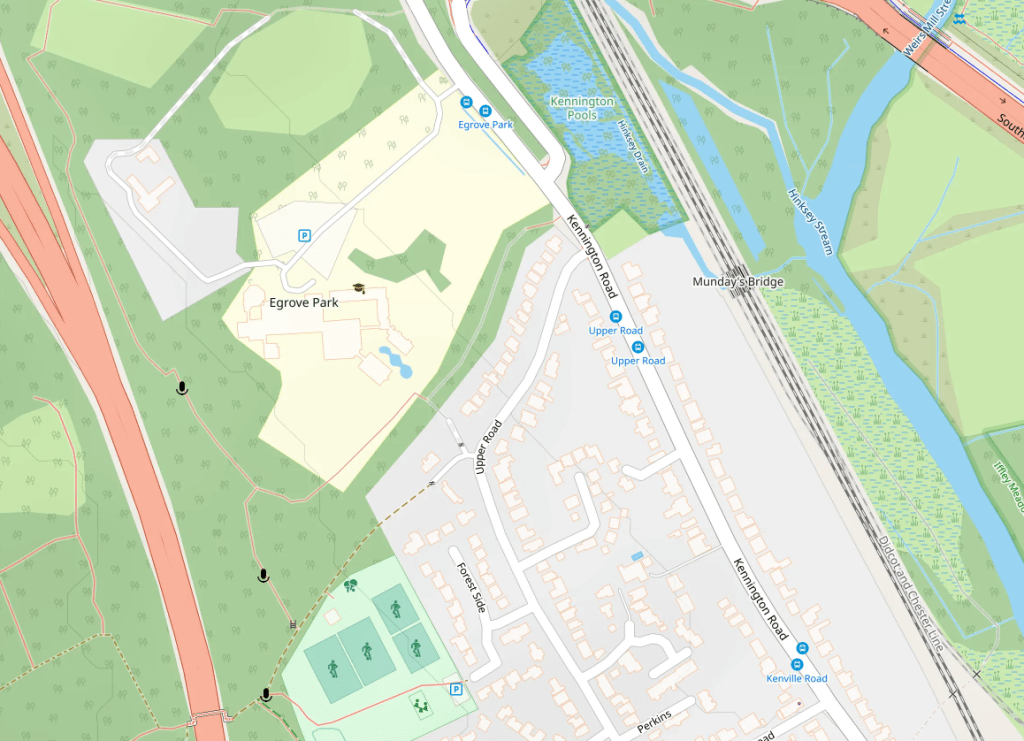

The wooded western part of the Egrove Park estate and the adjacent Bagley Woods provide roosting opportunities for Daubenton’s bats. To the east, Kennington Pools and the Hinksey stream provide wetland foraging opportunities over Hinksey stream, which connects to the Thames. The southern edge of the estate provides connecting linear features, include a shaded footpath that joins a wider network of paths in the woods, and a linear woodland edge following the line of the back of the houses in Upper Road. Daubenton’s bats use these features as a fly way at dusk and before dawn, to access foraging over water. This is confirmed by recordings and sightings at various locations as shown in the map. Presumably, the bats cross Kennington Road, though I didn’t confirm this.

I discovered this fly way by chance, when returning to my car after attempting to detect bats (not very successfully) at another nearby location. As I walked along the southern footpath, a rapid succession of bats flew past, close to my head. The detector confirmed they were Daubenton’s bats. I returned to this location and to the others shown on the map over subsequent nights to collect more data.

Setup for live video recording

In this setup, the goal is to film bats live and record their echolocation calls at the same time. The location for video recording was close to the second of the three microphone symbols on the map above.

I selected a narrow section of the shaded path where I expected the bats to fly, and aimed a tripod-mounted IR video camera at the narrow region. Thus, bats were constrained into flying through the field of view of the camera.

The video camera was manually operated, requiring me to start recording when a bat was passing through. This would require extremely fast reactions on my part to capture the bats. The alternative was to make lengthy continuous recordings that would require editing later. My solution was to manually to start the recordings, put to place a BatGizmo USB microphone a little way “upstream” of the camera, plugged into a tablet computer running BatGizmo app. The app was configured to record when triggered by the sound of a bat, and also to generated heterodyned audio output, routed to a USB speaker. I then placed a folding chair a short distance “downstream” of the bats, with and bluetooth speaker, next to the video camera. This allowed me to get a little warning of arriving bats, long enough to start video recordings manually.

The microphone, video camera and chair were placed to side of the path to avoid obstructing bats passing through, and to avoid bats modifying their usual echolocation sequence as they encountered an unexpected obstruction.

A limitation of this setup is that bats passed very close to the microphone so usually overloaded it as they passed by.

Setup for passive logging

The setup for passive logging was simpler. I used several BatGizmo loggers housed in Audiomoth boxes. These can be attached to branches, posts etc using simple straps, and are weather proof. I chose locations overlooking the expected flight path, with some space around the detector to avoid unwanted echos from branches, leaves etc. I pointed the detector across (not along) the flight path, set back from it by several metres. This had the benefit of recording the approach and fly past equally well and avoided overloading from very close bat passes.

Results

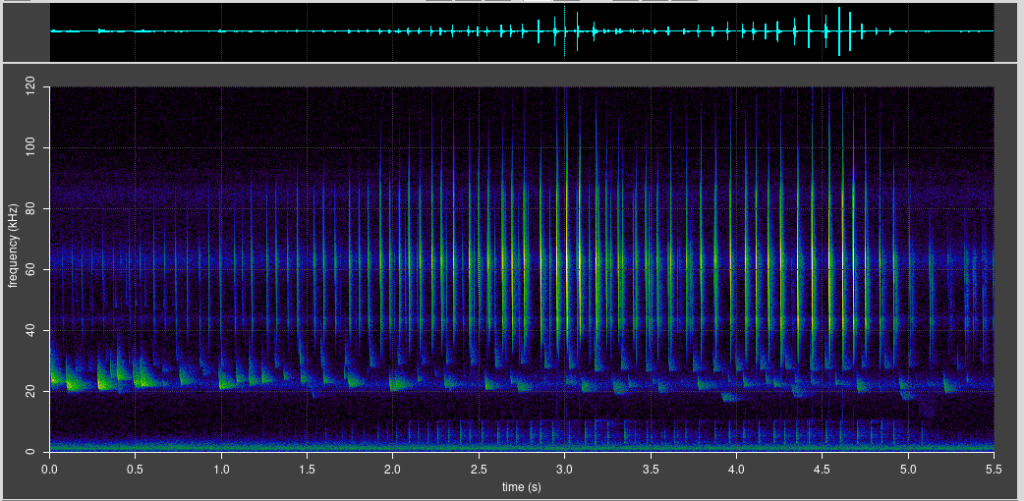

The setup for live recording worked well. About 25 Daubenton’s bats flew down the shaded path in an interval of about 20 minutes, starting at 10pm which was 35 minutes after sunset (June 2025). Mostly they flew through individually, though there were two cases of pairs of bats flying in rapid succession.

I could easily observe that all these bats were flying from west to east. No bats flew in the opposite direction. Large numbers of noctules were also recorded, foraging in the recreation ground a short distance away, and also some pipistrelles nearby.

The passive loggers confirmed this pattern of about 25 bats flying past from about half an hour after sunset. They also recorded the (presumed) return flights over about an hour from 3:15 am. Sunrise was at 4:46 am, so the return commute was about 5 hours after the outward flight.

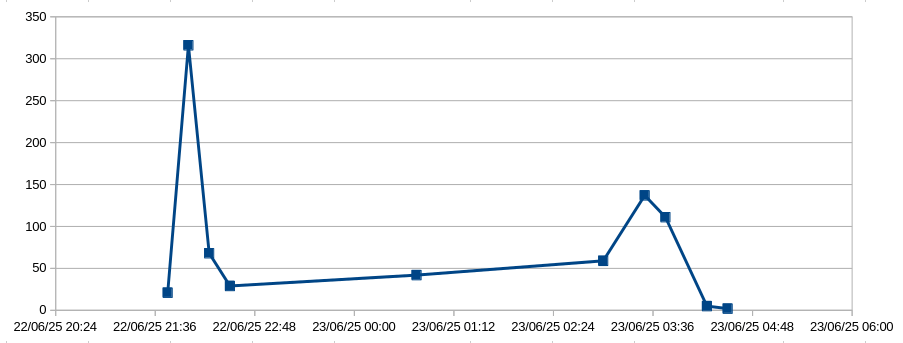

I did some analysis based on the number of Daubenton chirps that BatDetect2 automatically detected in 15 minute time buckets from sunset until sunrise on the following day. The outward and return commute are clearly visible as spikes, with the return commute more spread out than the outward.

Barbastelles at Egrove Park

The barbastelle bat (Barbastella barbastellus) is an insectivorous species that primarily feeds on moths, beetles, and other flying insects, often hunting in woodland edges and along hedgerows. It typically roosts in tree cavities, under loose bark, and in old buildings, often forming small colonies. Foraging occurs at low to medium heights, frequently in cluttered woodland environments, and barbastelles tend to fly slowly and quietly, using specialized echolocation calls adapted for detecting prey in dense vegetation. Commuting routes usually follow linear landscape features such as woodland edges, hedgerows, and streams.

I placed three passive BatGizmo detectors at the sites shown on the map, and left them for one or two nights. The results were striking and similar in each site. Each microphone recorded the usual woodland bats, but included very large numbers of barbastelles. The most northerly microphone was triggered about 125 times per night by barbastelles, the middle one about 200 times, and the southerly one about 25 times. For a species that is classified as “near threatened” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), these are very large numbers of detections.

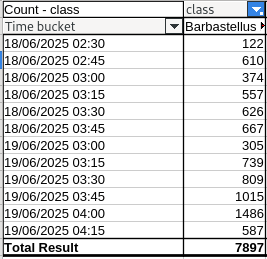

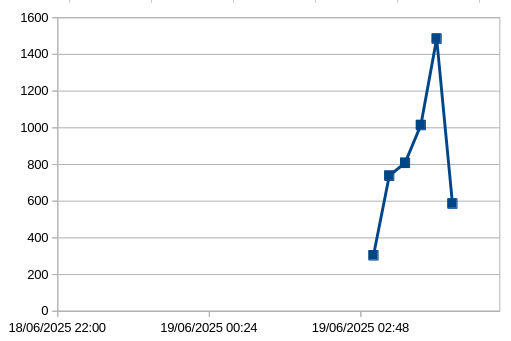

The raw data for the middle microphone site over two nights is shown below. The counts are the number of barbastelle echolocation chirps identified by BatDetect2 in 15 minute time buckets, which are labelled by their start time. Data from the other two microphone locations followed the same pattern.

A manual check confirmed that BatDetect2 identifications are reliable for Barbastelles.

The vast majority of detections were between 2:30 and 4:30 am, with almost none the rest of the time. On the dates in question, sunset and sunrise were at 20:20 pm and 4:43 am respectively. Barbastelle activity was therefore over a period of about two hours, ending abruptly at pre-dawn twilight, and peaking 45 minutes before dawn.

What is the meaning of this apparent barbastelle party? The microphones were all placed on the same north/south shaded pathway, so possibly the activity represents a commute from roost to foraging area. However, the numbers detected at each location were very different, and commutes usually consist of two activity peaks, one at dusk, one before dawn. So it doesn’t seem like a commuting pattern.

Perhaps there are maternity roosts nearby. In mid June, females will have formed smaller maternity roosts and may be going through a process of coalescence into larger roosts ready to give birth in July. They will be busy feeding themselves, but I would therefore expect feeding to occur throughout the night. This doesn’t seem to explain the burst of activity before dawn.

Males take no part in the raising of the pups, and typically live solitary lives foraging and roosting alone or in small numbers. This doesn’t seem to explain the predawn activity recorded either.

Barbastelles do engage in swarming activity, the primary purpose of which seems to be mating and location of winter roosts in the Autumn. But that doesn’t take place until late summer and later, so again, it doesn’t explain the predawn activity recorded.

Update: it has been observed elsewhere that females swarm in the vicinity of a maternity roost on returning from foraging, before entering the roost. At this point in the year, the maternity roost can be quite sizeable following coalescence. This certainly fits the pattern observed, so is the likely explanation. Thanks to Jane Harris of the Norfolk Barbastelle Study Group for this suggestion. I recommend her barbastelle write up, here.

Selected barbastelle spectrograms

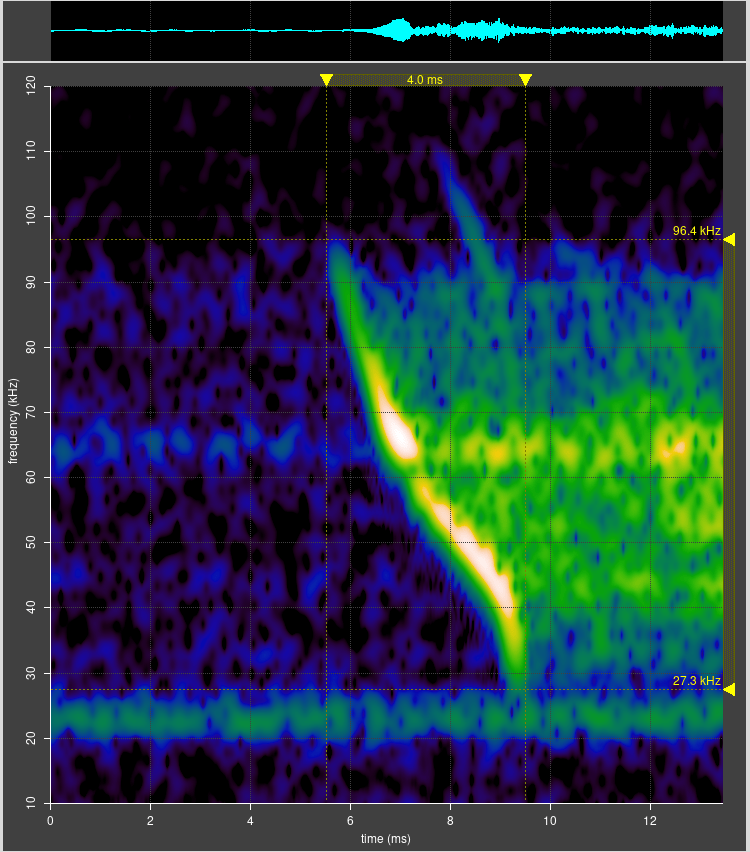

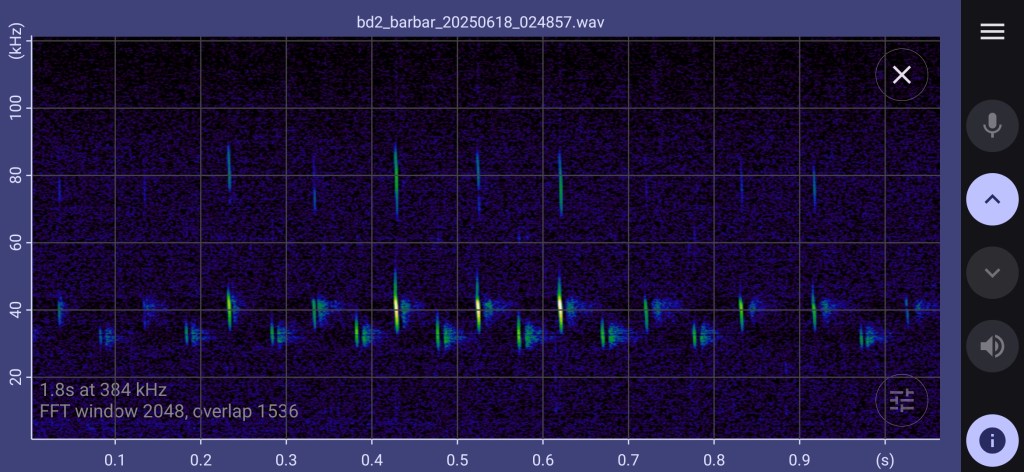

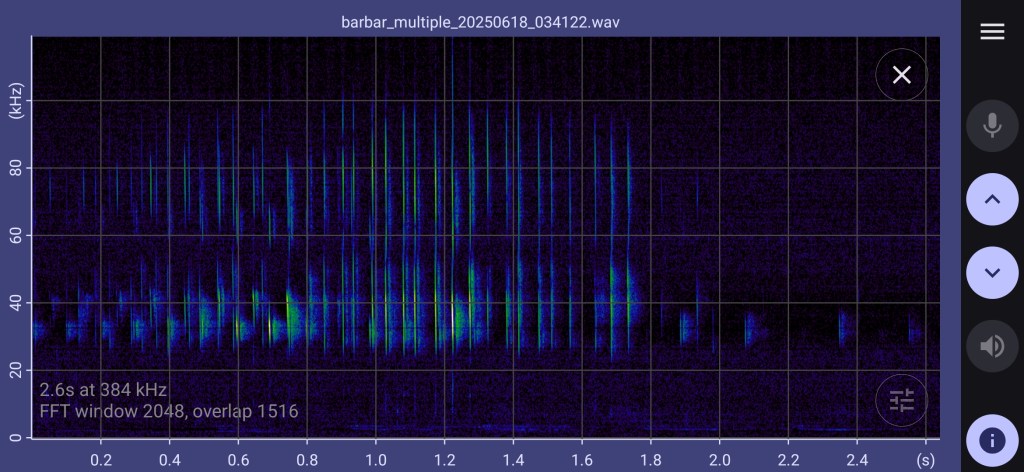

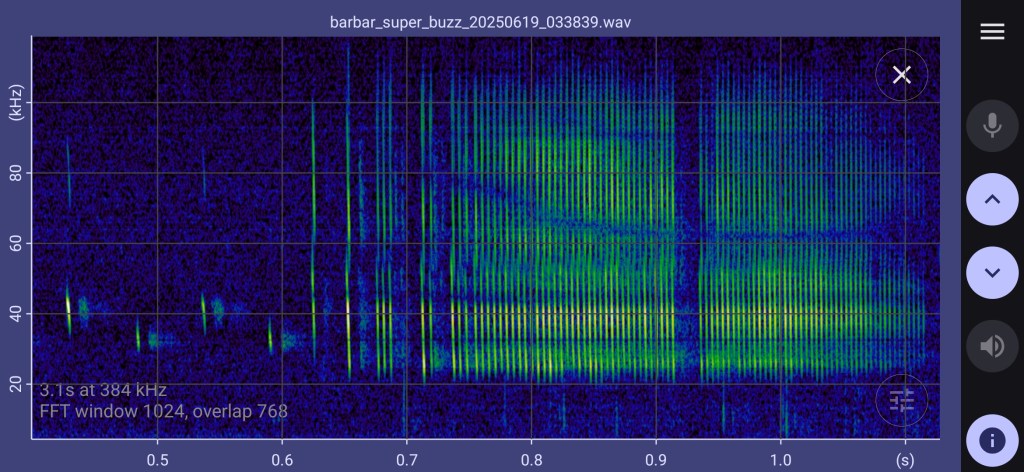

The spectrograms below show that barbastelles have a multiphase feeding buzz:

- Standard echolocation chirps gradually expand in bandwidth, and the distinction between upper and lower chirps disappears.

- Chirp bandwidth expands to 45 kHz to 30 kHz; a strong second harmonic harmonic appears in the range 90 kHz to 60 kHz; a weaker third harmonic extends over 100 kHz.

- The inter pulse interval settles down to about 20 ms (50 Hz). This pre buzz may revert to standard echolocation calls, or continue to a full buzz.

- In the full buzz, the inter pulse interval decreases to about 5ms (200 Hz). This may be sustained for half a second or more, possibly with short gaps before reverting to standard echolocation calls.

One response to “The Bats of Egrove Park (part 2): Daubentons and Barbastelles”

[…] The second part of the this blog series can be found here. […]