The second part of the this blog series can be found here.

Summary

Egrove Park provides a range of habitats including woodland, meadow and water. The site is managed for wildlife. Woodland areas provide roosting opportunities for bats, with paths and other shaded linear features providing access to extensive mature woodland and wetland habitats. In a series of visits in the summer of 2025, I made audio recordings allowing me to identify the follow bats with confidence:

- Common pipistrelle

- Soprano pipistrelle

- Noctule

- Barbastelle (many)

- Brown long eared

- Daubenton’s

- Brandt’s or Whiskered (indistinguishable by audio)

- Natterer

- Serotine

In addition, Leisler’s bats were also probably present.

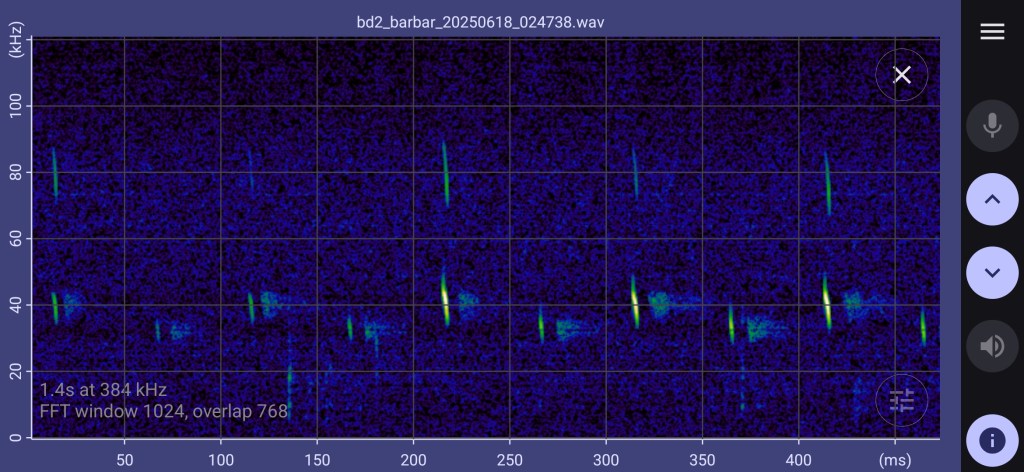

At one location, I recorded large numbers of barbastelle bat passes. Barbastelles are rare in the UK, mainly found in southern and central England and Wales. The large numbers recorded at one location possibly indicate the presence of a roost or swarming site.

Linear features along the southern edge of the site provide a shaded fly way for Daubenton’s bats commuting from Bagley woods to Kennington Pools and Hinksey Stream.

Note that the site is private, and my visits were made with permission. Do not visit the site without permission.

Credits

- Nick Bishop for the invitation and site access at Egrove Park.

- Merryl Parle-Gelling for advice and loan of an infra red video camera.

- Stuart Newson for supporting this activity with BTO pipeline credits and imparting his wisdom via the Bat Call Sound Analysis Facebook group.

Egrove Park

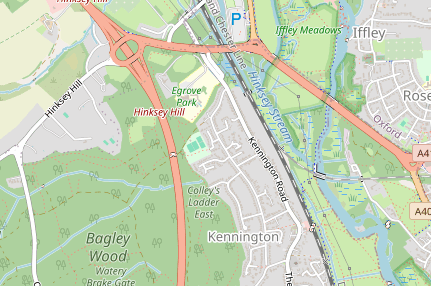

The Egrove Park site is in Kennington, just south of Oxford. A farmhouse and agricultural buildings were built in the early 19th century. In the 1960s, Oxford University redeveloped the land, constructing modernist buildings while some farm structures were retained and repurposed for accommodation. Today, historical elements blend with modern architecture, preserving the site’s heritage while serving educational and conference functions for the Saïd Business School.

The site contains a varied range of wildlife habitats which are actively managed for biodiversity, providing a sanctuary for numerous species such as deer, rabbits, squirrels, badgers, foxes and bats.

Situation

Egrove Park is situated in the angle between Oxford’s southern ring road and the A34, which form the northern and western edges of the site respectively. Both are large dual carriageway roads carrying significant traffic for much of the day and night. In general, bats dislike flying through open areas where they are vulnerable to predation, and are lucifugent, avoiding bright lights – dependent somewhat on specie. Movement of bats across these edges of the site is therefore likely to be very limited.

The southern edge of the site partly borders on the back gardens of houses in Upper Road Kennington, and partly on a grassy and open recreation ground. There is a public footpath running south west to north east along this edge of the site, providing a shaded linear feature that is an important bat fly way.

To the east, across a local road with limited traffic, is Kennington Pools, a former excavation site now managed by BBOWT as a wet woodland. Further to the east, across the railway, is the Hinksey Stream branch of the Thames, connecting with the Thames itself about a mile to the south. These features provide a wetland habitat which is important for certain species of bat.

Importantly, the south west corner of the site adjoins Bagley wood, which is a large area of mixed woodland owned and categorized as Ancient Semi-Natural Woodland (ASNW). Bagley Wood has an extent of about 570 acres. It is contiguous with Radley Large Wood to the south. These woods, together with the wooded western part of the Egrove Park site, constitute a large area of mature woodland, providing many roosting and foraging opportunities for bats.

Features of the Site

The site includes a range of buildings. The original farm house lies to the north west of the site and dates from the early 19th century. The former Templeton college, now part of the Saïd Business School, dates from the mid sixties and occupies the centre of the site. It is possible that the buildings contain features that bats could use for roosts, and there is a report that the original farm house has provided a roosting site for whiskered bats in the past. There was however no evidence for this at the time of my visits.

Buildings on the site are connected by paths which are brightly lit at night. In addition, the central buildings are surrounded by open grassy areas which are lit by flood lights mounted on the building. The reason for all this light is understandable, but unfortunately it is likely to discourage use of these parts of the site by bats. That said, a bat box located close to one of the pathways showed signs of habitation.

The most interesting parts of the site from the point of view of bats are the wooded areas. The western and southern edges comprised a band of mixed woodland. There are two large areas of meadow managed for wild life, and an open grassy area surrounding the main buildings and the site entrance to the east.

The wooded areas provide roosting opportunities for bats in holes, cracks and hollow parts of trees. They provide foraging areas for woodland specific bats. There are several broad paths through the woods which provide shaded linear features that bats can use for navigation and commuting between their roosts and foraging areas. These paths extend into Bagley Wood, providing a large interconnected area of native woodland that bats can readily access.

Summary of site usage by bats

The common pipistrelle is a highly adaptable bat, the UK’s most common. I detected foraging along the southern tree-lined footpath, garden edges, and woodland margins, also around the buildings where lighting was not too bright. They may roost in the buildings or trees on site.

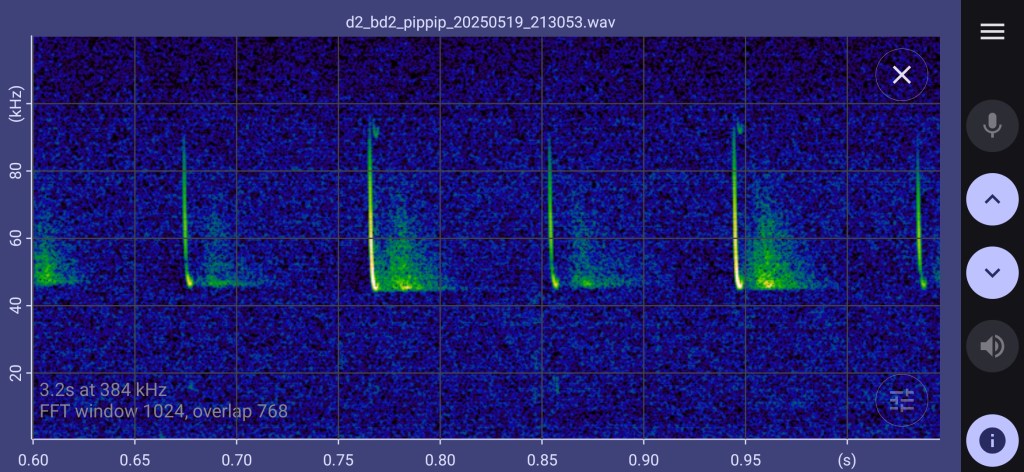

The soprano pipistrelle is the UK’s smallest bat. It is strongly linked to water, and likely to forage over Kennington Pools and Hinksey Stream, possibly commuting via the southern flyway from woodland roosts. I detected foraging in and around the wooded areas.

The Noctule is the UK’s largest bat; Leisler’s bats are their smaller cousin. They roost in mature trees. I recorded and observed noctules (and most likely Leisler’s too) foraging high over the meadows and front grassy area, also over the adjacent recreation ground. They emerge from their roosts shortly after sunset when there is still light in he sky, when they are clearly are visible to the eye.

The Barbastelle is a rare and interesting bat. They are relatively numerous at Egrove Park. They are likely to depend on Bagley Wood and adjacent woodland for roosting and foraging. Barbastelle’s bats strongly avoid lights and open areas. I recorded them in the woodland pathways.

Brown long-eared bats have very large ears allowing them hear the quietest sounds. Their echolocation calls are correspondingly quiet so they can avoid alerting their prey prematurely. This quiet call makes them a little challenging to record. Nevertheless, I recorded a good number of them at Egrove, mostly on the woodland paths. They are likely to roost in trees or buildings. They highly light-sensitive.

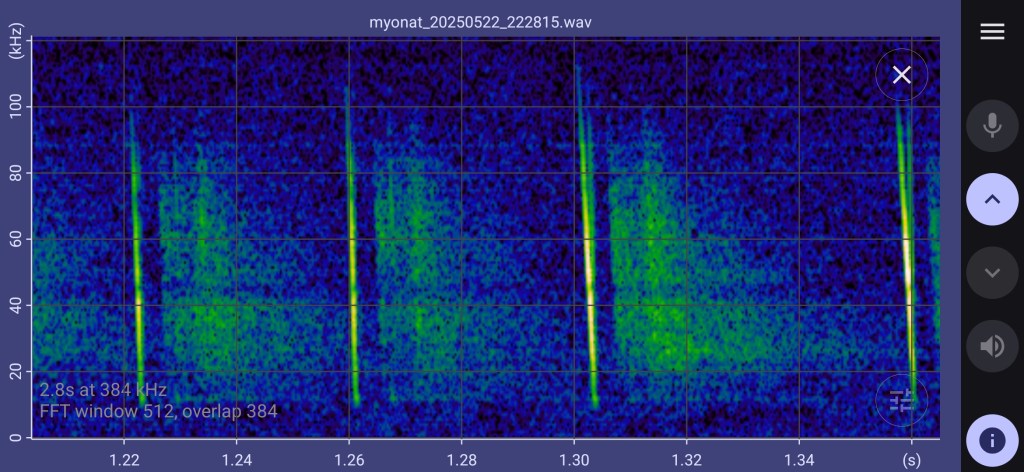

Daubenton’s bats are likely to forage low over water at Hinksey Stream and the Thames, possibly at Kennington pools. They most likely roost in the woodland, using woodland paths to commute east at dusk and back west before dawn. I detected large numbers of them using the southern footpath crossing the south of the Egrove Park on their commuting routes.

Brandt’s and Whiskered bats are virtually impossible to distinguish by recording alone, so I bracket them together. They are small woodland bats which forage along woodland edges and shaded paths, where I recorded them. They are likely to roost in tree cavities or buildings.

Natterer’s bats hunt in dense woodland and along tree-lined routes. They roost in trees or old structures, and avoid open or lit areas. I detected them flying along woodland paths.

The Serotine bat favours open grassy areas and woodland edges. They may roost in Egrove Park buildings or nearby houses. They tolerate moderate lighting. I recorded serotines in the woodland paths, feeding in one case.

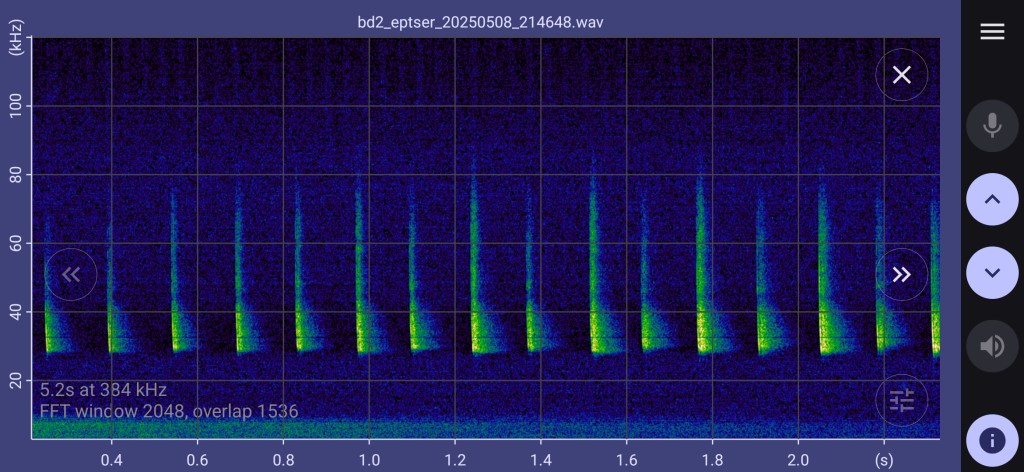

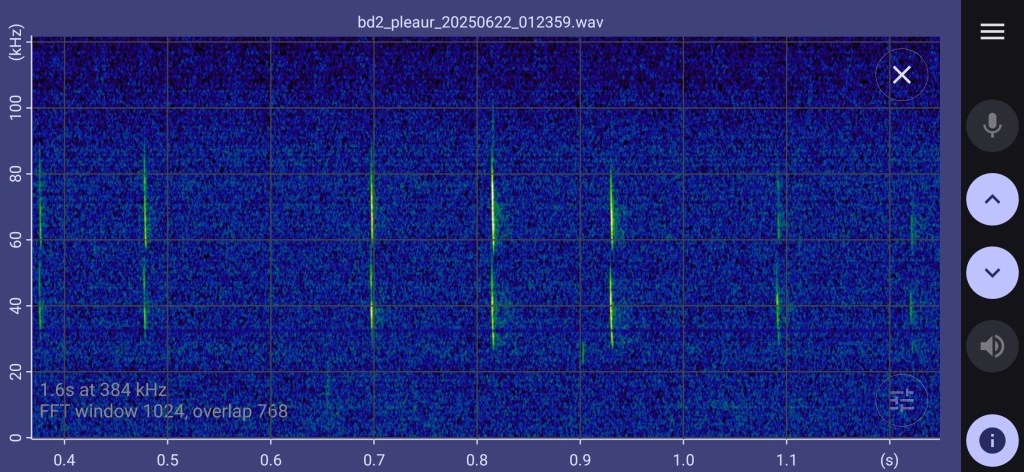

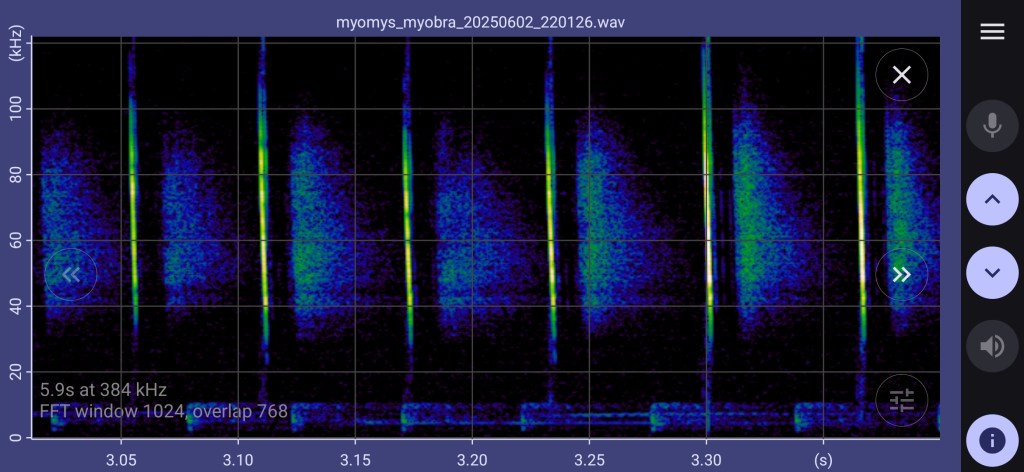

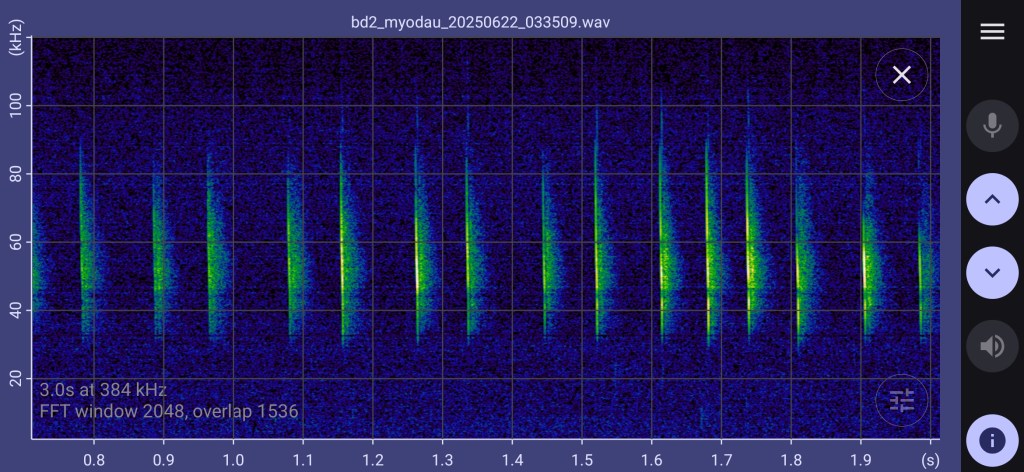

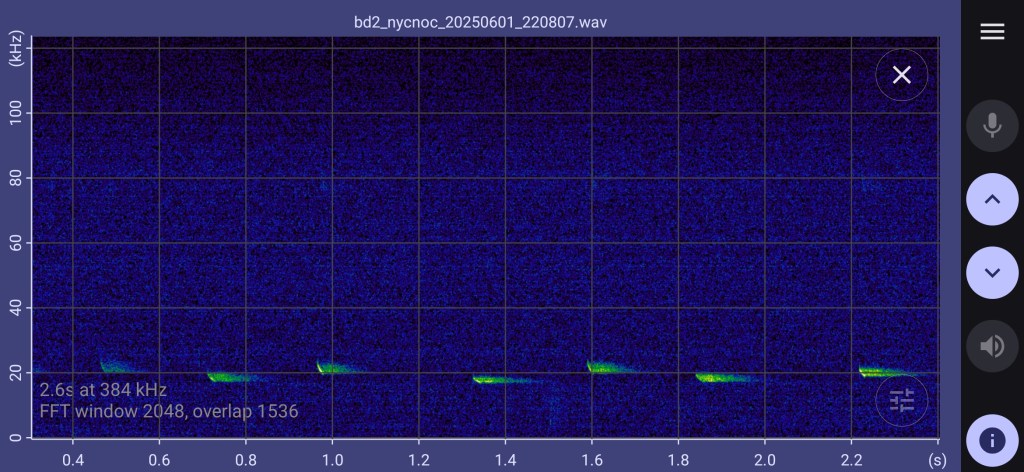

Selected spectrograms

Spectrograms are a visual representation of the sound a bat makes. The brightness represents the intensity of the sound. Time passes from left to right, and the pitch of the sound is represented by the height on the graph. That’s something like reading musical notation, where the highest note on the piano would appear at around 4 kHz in the spectrogram.

Equipment, approach and analysis

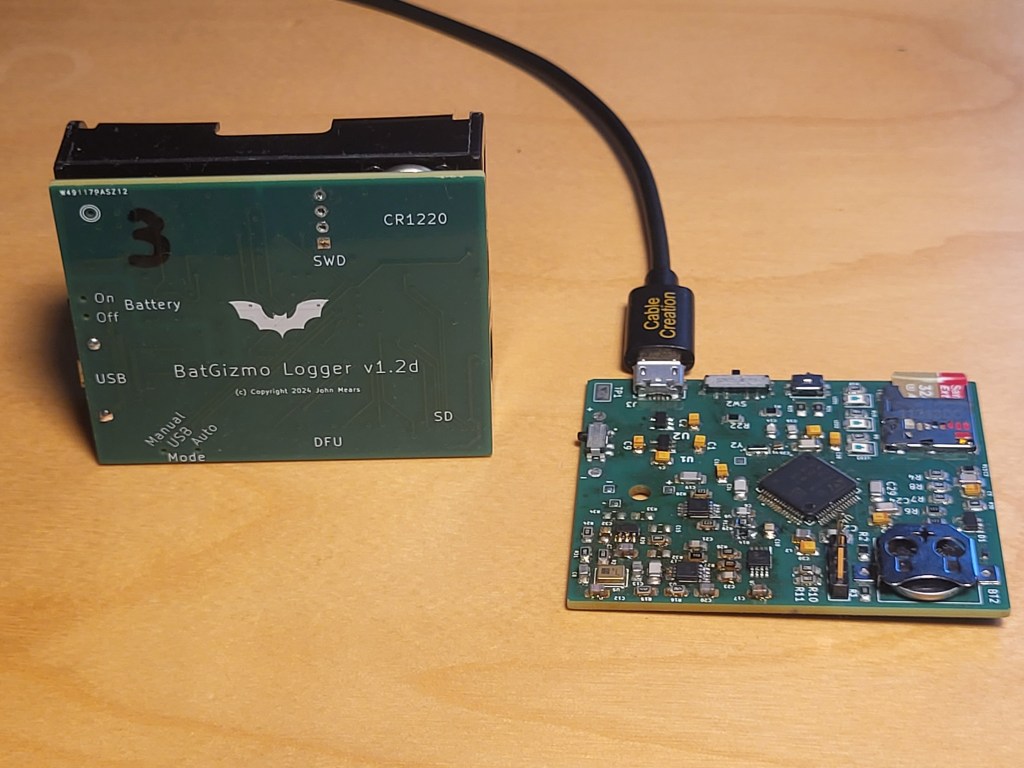

All the sound detection and recording equipment was of my own design and construction:

- A USB microphone of my own design and construction that I could plug into an Android tablet for live detection and recording.

- Four passive loggers, also of my own design and construction, housed in standard weatherproof Audiomoth boxes.

- BatGizmo open source Android app for displaying live spectrograms and making triggered recordings.

- Batogram open source desktop software for subsequent analysis of recordings.

My basic approach was to identify a variety of locations in the site where bats were likely to be be found. I spent about an hour from sunset at each location doing live detection with the USB microphone and tablet to see if bats were indeed present. If so, I set up unattended overnight loggers to make triggered recordings to SD card. As far as possible, detector positions were chosen to be clear of surfaces, trees and shrubs that might reflect sound and result in a unclear recording.

In some cases I attached a detector to a 3m pole with guy lines.

In other cases, I attached detectors to tree trunks and branches.

In all cases I noted dates and exact locations in a spreadsheet for future reference, and so that I could find the detector the next morning.

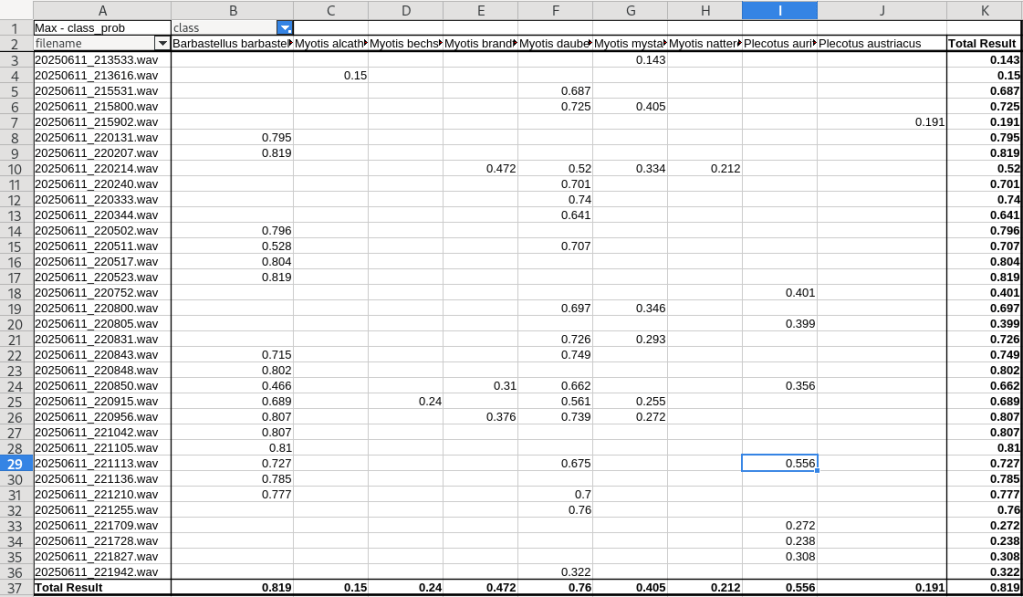

The result of this activity was over 15,000 recordings from 13 site locations on 14 occasions. That is too much data to analyse by hand, so I used the following semi-automated approach:

- Copy the recordings from SD cards and the tablet computer to folders on my desktop computer.

- Use BatDetect2 open source software for initial analysis. This software uses AI to categorise bat recordings. It has certain limitations, such as having no training on social calls, but still provides a very useful first pass over the recordings.

- Manually inspect a proportion of the BatDetect2 verdicts. It is very reliable for easily recognised bats calls such as pipistrelles, barbastelle; somewhat reliable for the big bats (noctule, leisler and serotine), and not very reliable for myotis bats.

- Upload some or all of the recordings to the BTO Pipeline, which gives more reliable verdicts than BatDetect2. Typically I submitted all files that BatDetect2 thought contained some kind of bat.

- Do detailed manual inspection of all recordings with myotis bat verdicts, quick inspection of big bat verdicts, and cursory inspection of pipistrelle and barbastelle verdicts.

I created Python scripts to automate much of the process above.

One response to “The Bats of Egrove Park (part 1): Diversity”

[…] previous blog describes how in the summer of 2025 I spent time at Egrove Park, discovering how the site is used […]