Dore Abbey is confusingly to be found by the village of Abbey Dore, near the river Dore in the Golden Valley, Herefordshire, close to the border between England and Wales. The name probably originates with the Normans confusing the Welsh dŵr (water) with the French d’or (of gold). The same naming confusion exists in connection with the Douro valley in Portugal and Spain.

The Welsh borders provide perfect countryside for walking, cycling and drinking cider, so when I was invited by the Craswall players to play double bass in a concert in the Abbey, I quickly agreed. I packed my bass, my bicycle and my bat detector. And some other things.

Bats at the Abbey

It turns out that Dore Abbey hosts a population of bats in the chancel attic – in particular, some rather rare lesser horseshoe bats (LHBs), but also some Natterers bats. There is a video here showing LHBs inside the attic getting ready to leave and go foraging.

I had a spare hour after sunset the evening prior to the concert, so I took the opportunity to see what I could detect in the church yard. I was in luck.

Lesser Horseshoe Bats

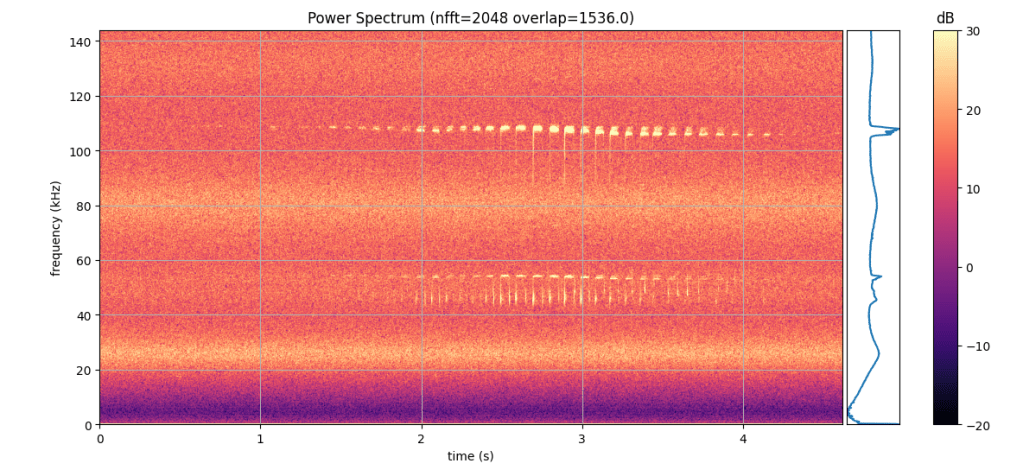

LHBs echolocate at a very high frequency – around 110kHz. This was a good test for the detector, my own design, previously untried at such high frequencies which are about 3 octaves higher than the limit of human hearing.

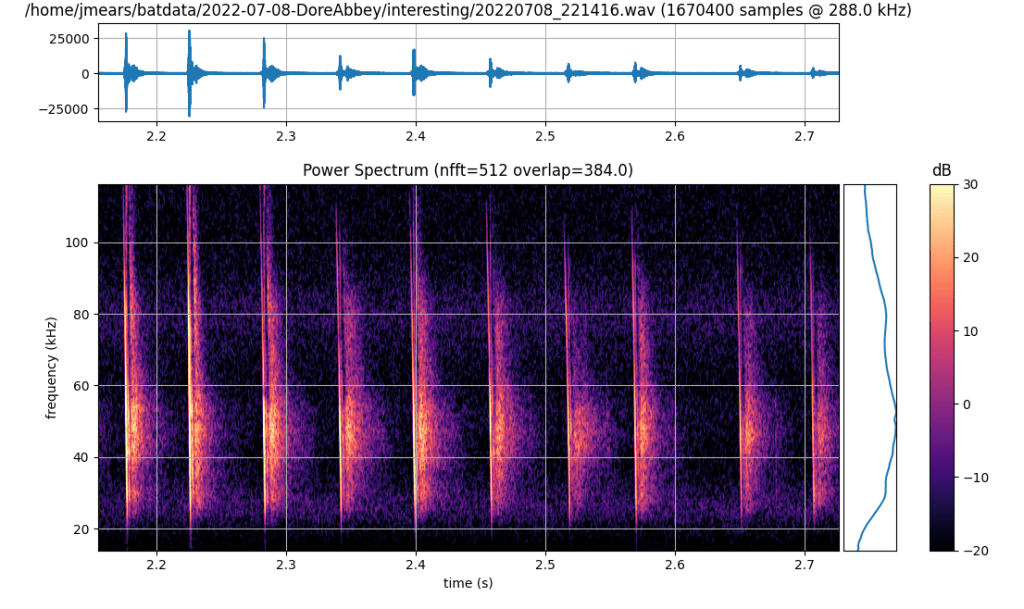

LHBs are small bats. They have an extravagant and rather odd nose flare. Unusually for British bats, they use their noses emit echo location sounds, not their mouths. Each echo location call looks somewhat like a staple, with a rapid rise and fall either side of a flat (quasi constant frequency) section at around 110kHz, lasting about 50ms, repeating about 10 times a second. Their unmistakable calls are very directional, so are best detected by positioning a microphone in the likely line of flight.

The slight variation in pitch seen can plausibly be explained by Doppler shifting – a speed flight of the order of 10 m/s could explain the variation seen. If you examine the spectrogram closely you can see that even when the pitch drops a little towards the end of the sequence, faint echos can still be seen at the original pitch. This would be the case if there are reflections from stationary surfaces around the bat, which would be unaffected by Doppler shift.

Notice that the 110kHz sounds are mirrored by similar fainter sounds at 55kHz, half the frequency. In fact, the sound at 110kHz is the second harmonic of the actual call made by the bat, which is at 55kHz. LHBs therefore seem to have a way to double frequency. Speculating wildly, this could be achieved via an acoustically non linear element, with something resonant, maybe a cavity or accoustic horn, to amplify the component at 110kHz. You read it here first.

When heard on a heterodyne detector tuned a little below 110kHz, the call is unmistakable, sounding like a low budget sci fi sound effect.

Natterers Bats

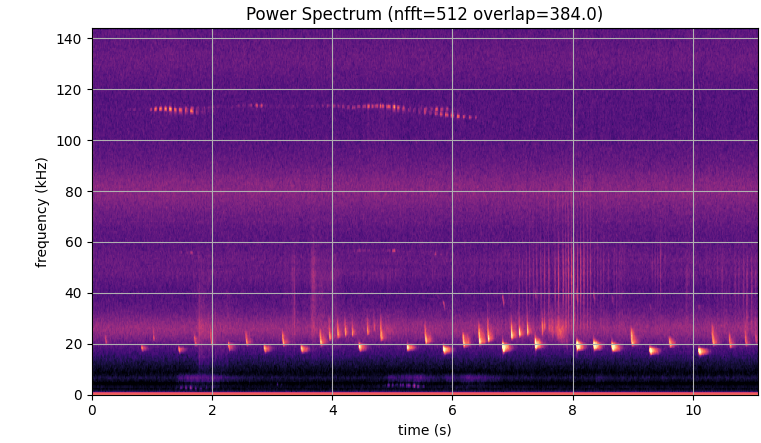

Natterers bat calls were also present. These bats are of the myotis family, which are notoriously hard to tell apart. However there are some clues that make these likely to be Natterers calls:

- The calls are extremely wide band, spanning a frequency range from below 20kHz to above 110kHz.

- Each chirp is very straight – no sign of any S shape characteristic of other myotis bats such as Daubentons.

- Natterers have been documented as living in the Abbey.

Other Bats

Of course, other more common bats are to be found around Dore Abbey, somewhat upstaged by the star bats described above. There were plenty of pipistrelles and a noisy noctule about.

One response to “The Bats of Dore Abbey”

Dore Abbey is also famous as the source of my profile image. That’s not as interesting as bat detecting though.